Report Summary

- The Ministry of the Interior, through the prison administration, continues to discriminate among prisoners, based on the prisoner’s background and the reasons for imprisonment. Political opposition prisoners or critical voices who belong to the January Revolution are subjected to abuse, repression, and denial of many rights guaranteed by the constitution and the law, such as visiting or receiving food and the right to make phone calls, or receive health care, and even depriving them of attending their detention renewal sessions.

- Meanwhile, the same ministry, through the same “Prison Administration” and sometimes in the same prison, provides care, entertainment and services to convicted prisoners who belong to the former regime or those accused of financial and corruption cases.

- The Public Prosecution often overlooks the violations that the Ministry of Interior practices against prisoners. It neglects investigating complaints submitted to them, and extend the detention of pretrial detainees without their presence. It also overlooks detaining prisoners beyond the maximum legal terms. At other times it circulates (recycles) the defendants and detains them pending new cases, even without strong evidence or justifications, which makes it as if it is using pretrial detention as a punishment.

- The Ministry of Interior or state agencies do not recognize the existence of political prisoners in the first place, although many prisoners and detainees, some of whom spent years behind bars, only for a post on Facebook, an article on a website, a peaceful demonstration, or a statement to a TV channel.

- While the law and the constitution oblige state agencies to work on equality between prisoners, many prisoners’ families file cases to oblige the Ministry to allow them to visit their imprisoned relatives. This happened with the family of lawyer Essam Sultan and former President Mohamed Morsi. There also had been reports submitted about blogger Mohamed Oxygen’s denial of visitation. Other prisoners were denied the conditional or health release, such as the Brotherhood leader Mahdi Akef and Dr. Essam El-Erian, both died in prison. On the other hand, other prisoners such as former President Mubarak, his sons and some of his regime figures who were imprisoned for short periods of time were visited either by their relatives or friends. Others who were accused of murder were released, such as Hisham Talaat Mustafa or those accused of thuggery, such as Sabri Nakhnoukh.

- The Ministry of Interior uses complicit human rights institutions, such as the National Council for Human Rights, to obscure and hide the repression and to beautify its image. The state also employs most media outlets, which have come under its control, to present a fake image of the prisoners’ deteriorating conditions.

- The number of new prisons for which establishment decrees were issued since the January revolution, within 10 years, has reached 35, added to the 43 main prisons that were operating before the revolution, bringing the number of main prisons to about 78.

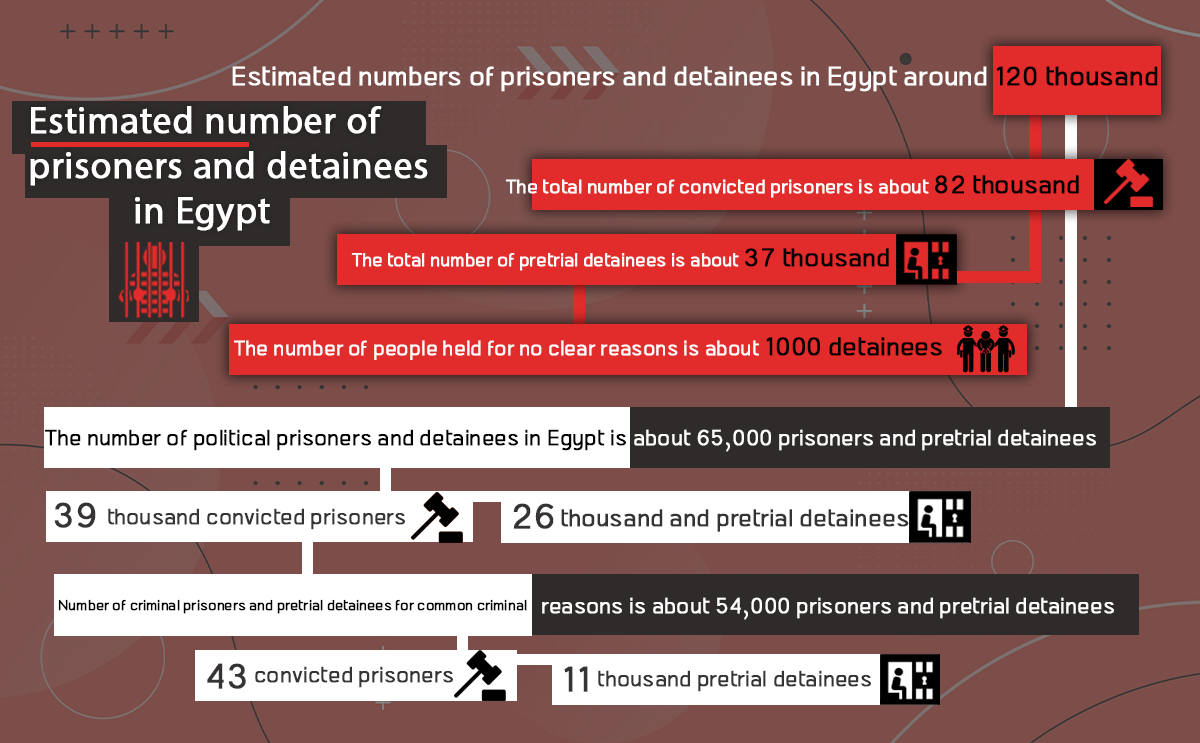

- The Arabic Network for Human Rights Information estimates that there is about 120,000 prisoners and detainees held in Egypt until the beginning of March 2021. The number includes about 65,000 political prisoners and detainees, and 54 thousand criminal prisoners and detainees. There is also about a thousand detainees held which we were unable to figure out the reasons for their detention.

- Out of those imprisoned and detained, the number of convicted prisoners reached a total of about 82,000, while there is about 37,000 pretrial detainees.

Contents:

- Before we begin: Stories about prisons and prisoners

- Definitions and terminology

- Methodology

- Legal developments related to prisons

- Examples of violations against prisoners and detainees

- Using COVID-19 to oppress prisoners

- Preplanned visits to prisons to beautify the image of the interior ministry.

- Numbers of prisons in Egypt before and after the January revolution.

- Estimated numbers of prisoners and detainees in Egypt.

Before we begin:

- Two stories about a prison within the same month; January 2021

The first story:

“We were 16 staying at two buildings that have the capacity to hold up to 3000 people. I entered and met Hisham Talaat Mustafa, he built a mosque inside. Ahmed Ezz built a gym and a spa with the latest equipment. There was also table tennis and pool. There I met also Alaa Mubarak who brought me a TV, and Gamal Mubarak gave me a refrigerator. We used to play football together, I was in a team and Gamal was in another team including police officers. Habib Al-Adli used to join the games as a referee. He asked about what happened to me, and said it was a wake-up call, so I have to think carefully and figure out what I did. I found that there was a reason! I only spent 6 months out of my 5 years sentence”

The second Story:

It was difficult times since I have entered, I was stripped off my clothes, my hair was shaved, then I was taken to rooms called the “newcomers”. I was placed in the political detainees ward for ten days, and then I entered the cycle of detention renewals for 45 days. I was moved many times to the disciplinary cell and beaten by informants. With the repeated renewals I was fed up; so my friends and I went on a hunger strike.

We were sitting in a room of approximately 12 square meters in which there was one bathroom. There were about forty detainees in that room including some forcibly-disappeared referred from different police stations. They brought them to this place to be accused of new crimes in different cases. We used to sleep in turns, ate only bread, and sometimes the prisoners who were visited by their relatives pitied us and gave us some food.”

- The story of two imprisoned presidents

On 17 June 2019, former President Mohamed Morsi died in custody at the age of 68.

Eight months later, and on 25 February 2019, former president Hosni Mubarak died in a military hospital, at the age of 91, the two men ruled Egypt, with a huge difference in the ruling period. The former remained in office for nearly thirty years, while the latter had barely completed his first year in office.

Although the two former presidents were imprisoned, their prison conditions were marred by discrimination and inequality.

- Hosni Mubarak enjoyed residence and medical care at the International Center during his imprisonment. It is one of the most important hospitals in Egypt. But Morsi was deprived of adequate care and punished by solitary confinement.

- Hosni Mubarak received many visits, not only from his family members, who had the right to visit him, but also from acquaintances, friends, and supporters. Some of the visitors were even not Egyptians. On the other hand, the family of Mohammed Morsi was forced to file a lawsuit only to be enabled to visit him, even though it is their legally granted right.

- Hosni Mubarak was being transported during his detention to the trial at the Police Academy in a plane, while Morsi was being tried at the Police Cadets Institute, after being transported in a car and from within a glass cage.

- After his death, Hosni Mubarak had a military funeral, although he was ultimately convicted of dishonorable financial crimes. Morsi was not only deprived of the military funeral, but also of burial in his family’s burial ground, and was buried in the “Al-Wafa Wal Amal” cemetery in Nasr City, Cairo.

Definitions and terminology

The definitions of an arrested person and a prisoner are often confused, as well as the term pretrial detainee and a detainee. People also mix between a central prison, a General prison and the Leeman.

Here are the definitions of those words:

- Prisoner: every person, sentenced to prison by a judge, and ought to serve his/her term “legally” in a general or central prison.

- Pretrial detainee: every person accused of a crime “whether real or fabricated” and is being held in pretrial detention by a decision of the prosecution or an investigating judge or a judicial counseling chamber pending investigation. Legally, this person ought to be held in a central prison. After amendments to prison laws, the interior ministry now is able to hold pretrial detainees in general prisons with convicted prisoners.

- Detainee: Is the one whose freedom has been restricted by an arrest order issued by the President of the Republic or his representative or the Minister of Interior as an “administrative and not a judicial body”. The arrest order is normally based on the state of emergency, and in this case only the arrested person is called a “detainee” because he is held by an administrative rather than a judicial decision.

Detention in huge numbers was common under Dictator Hosni Mubarak’s 30-year rule. Most of those whose freedoms were restricted have been considered detainees. The term has become popular and is still used today, among journalists or even lawyers and ordinary citizens. The confusion is partly due to the similarity between the conditions of pretrial detainees, political prisoners, and detainees. The Ministry of Interior and the media outlets they control, attack anyone who uses the term “detainee” to describe a pretrial detained person or a convicted prisoner. They claim that there are no detainees in Egypt, while the public and the media use this term as it describes the “actual” situation for many arrested people even though their detention enjoys a legal status on paper.

- Arrested: is every person whose freedom has been restricted, whether legally as a “prisoner, detainee or in pretrial detention”, or unlawfully, such as in cases of arbitrary detention without a decision or official papers. The arrested might be held in legal places of detention “prisons, Leemans, private prisons, or Military prisons” or in illegal places of detention, such as “Security camps, headquarters of the National Security Investigations, and others.”

- Forcibly disappeared: is every person who has disappeared, and there have been indications of the involvement of official agencies, such as the Ministry of Interior or others, in his detention while denying such detention for days, months, or even years. Neither the Ministry of Interior nor the Public Prosecution make any effort, to investigate the facts of forced disappearance or to search for the people reported to be forcibly disappeared. The fact that a disappeared person re-appears after days or months does not mean that he was not forcibly disappeared.

- Central Prisons: Are prisons subject to the administration of security directorates not the prisons’ administration. They are not subject to judiciary supervision.

- General Prisons and Leemans: prisons subject to the prisons’ administration in the interior minisrty and subject to judicial supervision.

- Secret Prisons: every place where people are being held illegally such as security forces campus, headquarters of the National Security Investigations Department. Police stations can be considered secret prisons, if people are detained there without registering their data in the official records.

- Political Prisoner: every detained person, whether imprisoned or detained, because of cases related to public affairs, from those held against the backdrop of a comment or a post on Facebook, or a tweet, or writing an op-ed, criticism, a drawing or a photo, even those who believe in violence, whether inciting to or using it, all the way to those who demonstrate, join a sit-in, or strike for a demand or against an incident. They all deserve a fair trial and humane non-degrading treatment. However, in the event that they are prisoners of conscience, then they deserve immediate freedom.

- Prisoner of conscience: is anyone who has been detained and deprived of his freedom because of their peaceful expression of an opinion that does not entail incitement to violence or its practice. Such a prisoner deserves immediate unconditional freedom. Every prisoner of conscience is a political prisoner, but every political prisoner is not necessarily a prisoner of conscience.

- The ordinary “criminal” prisoner: everyone whose freedom was restricted for criminal reasons that are not related to public affairs, such as theft, drugs, fraud, beating, etc., and such a prisoner also deserves a fair trial and humane treatment.

The report methodology

- This monitoring report is based on the official decisions/decrees regarding establishing new prisons issued by the Minister of Interior and published in the Official Gazette. As well as the statements by state officials, and what the media publishes in print newspapers, websites or television channels. ANHRI was keen on using mainly state-owned media outlets or those close to the regime, most of which are controlled by the state, whether directly or through companies running them, where there isn’t doubt with regard to their commitment to the state officials’ declarations, and therefore it would be difficult for the ministry of interior or the official bodies to accuse such outlets of belonging to the opposition, especially the Muslim Brotherhood. The report also relied on international media outlets known for their professionalism.

- The report also relies on numerous interviews and meetings with families of prisoners and pretrial detainees, as well as former prisoners or defendants. As well as monitoring and following up on the laws, legislations and various decisions related to prisons, in addition to meetings with some employees of the Ministry of Interior and experts who prefer to remain anonymous.

- The report includes an update to the content of the previous report on prisons by ANHRI published in early September 2016, under the title “There is Room for Everyone… Egypt’s Prisons Before & After January 25 Revolution”. [1]

- Although the report focuses on the state of prisons and prisoners during 2020, it also addresses some phenomena and issues that came up during the last five years, since the previous report was issued in 2016 until today.

- The report attempts to answer what ANHRI considers to be the most important questions, which clarify the picture to a great extent such as:

- What are the most prominent legislations, laws and decisions related to prisons issued recently?

- What are the most common violations in prisons and against prisoners?

- What is the impact of the COVID-19 pandemic on prisoners in Egypt?

- How many prisons are there in Egypt now?

- How many prisons were there before the January 25 revolution, and how many prisons were established up until the previous report by ANHRI in 2016? How many prisons have been built since 2016 until now?

- How many prisoners are there in Egypt? And how many of them are political prisoners? And how many are criminal prisoners?

- How many pretrial detainees are there in Egypt?

First: Legal developments related to prisons

- Laws limiting pretrial detention have not seen the light since 2017.

The head of the Parliament’s Human Rights Committee, Alaa Abed, demanded repeatedly during 2017, 2018, and also in 2019, to replace pretrial detention in cases that do not pose a threat to national security and public security. He suggested using house arrest instead. He mentioned that his motive was not out of respect for human rights, but in order to save 10 to 20 billion Egyptian pounds annually for the state. Furthermore, he stressed that the overcrowding of prisons suggests that there is a crackdown on freedoms in the country and also consumes a part of the general budget. ([2])

- The law canceling the option to release a prisoner after spending half the sentence

In January 2020, the Parliament’s Legislative and Constitutional Affairs Committee approved a draft law submitted by the government on organizing prisons. The law aimed to cancel the half-term release, for some cases, including “gatherings, drugs, money laundering and terrorism”. The government claimed that it aims to correct the course of Law No. 6 of 2018, and to confront the dangerous elements in cases of gathering, drugs, money laundering and terrorism, as they constitute serious threats to national security from a governmental point of view. So they have to be excluded from the possibility of half-term release for the sake of the state and public interest.

In March of the same year, the aforementioned bill came into effect after presidential decree by President Abdel Fattah El-Sisi, No. 19 of 2020. ([3])

- The Public Prosecution directs its members to replace detention with precautionary measures:

In May, the Public Prosecution ordered its members representing it before the courts handling pretrial detention decisions, to demand replacing these orders by other precautionary measures alternative to pretrial detention whenever possible. ([4])

However, it remained a statement that has no effect in reality. Rather, the periods of pretrial detention and rotation/recycling have increased, as we will see later.

- An extension to deadlines of procedures, grievances and lawsuits, that does not cover pre-trial detention

In June, Prime Minister Decision No. 1295 of 2020 was published in the Official Gazette – Issue 26 bis (B) and it states:

The period from 17 March 2020 until the date when the Prime Minister Decision No. 1246 of 2020 comes into effect, is considered a suspension period. This is with regard to dates for statutes of limitation, procedural dates for mandatory grievances, lawsuits and judicial appeals, and other dates and deadlines stipulated in the laws and regulatory decisions.

This decision does not apply to the deadlines and dates for pretrial detention and the appeal of criminal judgments issued against imprisoned individuals in implementation of those rulings.

Second; Examples of violations against prisoners and detainees

- Using pretrial detention as a punishment

The Court of Cassation says: “… and even if the basic principle is that the court may rely in forming its belief on investigations as it is reinforcing the evidence as long as it was up for discussion, but it is not valid on its own to be considered as evidence proving a crime …”.

Casation court –criminal- appeal No.2421- for the judicial year 58- the session on 3 November 1988

Despite this explicit ruling that it is not permissible to rely on investigations only to use preventive detention, thousand have been and are being held for long periods of pretrial detention without evidence or valid presumptions, such as:

- Journalist and former prisoner of conscience Hisham Jaafar, who was held in pretrial detention at the end of 2015 until the spring of 2019, when he was released after about three and a half years.

- Journalist and editor-in-chief of Masr Al-Arabia Adel Sabry, who has been imprisoned for more than two years. He was arrested in April 2018 and released in July 2020, having served 27 months in pretrial detention without evidence.

- The ongoing detention of young journalist “Moataz Wadnan” since February 2018 until now, without evidence and based only on investigations, due to an interview he conducted with Counselor Hisham Geneina about corruption in Egypt.

- There are many other instances of individuals still being held in pretrial detention without evidence and based only on investigations such as: journalist Khaled Daoud, lawyer Ziyad Al-Elemy, human rights lawyer Amr Imam, Ola Al-Qaradawi and her husband, as well as activist and blogger Alaa Abdel Fattah, video blogger Mohammed Oxygen, and others.

- Deprivation of rights guaranteed by the law to prisoners and pretrial detainees

- Deprivation of the right to make a phone call

If you like to read the accidents section in newspapers, you will read from time to time the title “A mobile phone found in Prison” It usually implies that a mobile phone was seized, or an attempt to smuggle a phone for a prisoner was uncovered, and that legal measures were taken.

This is what is called the upside down pyramid! In fact, according to the law, those who deny prisoners the right to make phone calls should be held accountable and punished, not those who seek to enable them to exercise their right. The Ministry of Interior violates the law by not implementing Article 38 of Law 106 of 2015 that provides this legal right, and the MoI also punishes whoever tries to access this legal right.

- Unlawful solitary confinement

There is a clear straight forward text that; Solitary confinement is a punishment, which should not exceed 15 days, and that the prison doctor should visit the punished person on a daily basis.

This is Article 44 of Law 106 of 2015 on Prisons. But it is not the reality in prisons. Solitary confinement is being used in a semi-systematic way to abuse prisoners and pretrial detainees for prolonged periods. And of course there are no visits or follow-up from the prison doctor.

Among the many examples that have been punished with solitary confinement:

- Mohammed El-Kassas

He is the Vice-President of the Strong Egypt Party. He exceeded the period of pre-trial detention. He was arrested in February 2018, and spent more than 3 years in unjust prolonged pretrial detention. During this period he was subjected to many months of solitary confinement, without holding the ones for such an abuse accountable, in Maximum Security Prison 2, Tora.

- Ola Al-Qaradawi and Hussam Khalaf

Ola Al-Qaradawi, “daughter of Islamic preacher Yousef al-Qaradawi,” and her husband are about to complete four years in pretrial detention. They are accused of joining a terrorist group, but there is no valid evidence to prove the accusation. They are being actually abused, not only by exceeding the period of pre-trial detention, but also through their solitary confinement. Within the period of their continuous detention they were punished by solitary confinement for more than a year and a half each. Ola in Qanater prison while Hussam in Maximum Security Prison 2 in Tora.

- Prevention and denial of visitation rights

According to the law, every prisoner has the right to visits by his family at least twice a month, as well as the right to meet with his lawyer. But in order to abuse prisoners and punish them for their opposition to state policies, this right is wasted for many of them. Some of them had to resort to the judiciary, only to oblige the prison administration to respect the law and respect the visitation rights. Examples:

- Lawyer Essam Sultan, was arrested since July 2013 and inmate in Scorpion Prison. Essam was prevented from visiting for years, prompting him to file a lawsuit before the Administrative Court challenging the Ministry of Interior, as the prison administration continued to prevent his family from visiting him. The court granted him the visitation rights and described visitations prevention as a violation of the provisions of the constitution and the law. He was only allowed to receive his first visit in 2015, and it lasted only for a few minutes.

- Mohammed Oxygen, the well-known video blogger, is being punished only because he broadcast interviews with opposition and human rights figures. The videos and interviews do not include any crime, but only political and human rights criticism. He spent more than three years imprisoned. He was out for only two months in the summer of 2019. Since his re-arrest, he is denied visitation rights despite the reports submitted to the public prosecutor, the deterioration of his health, and the threat to his life.

- The prosecution also violates the rights of pretrial detainees by preventing appeals

According to the Code of Criminal Procedure, every defendant has the right to appeal the order issued to extend his detention at any time. If his appeal was considered and rejected, he is not entitled to file another appeal for thirty days.

This appeal should be subject to appointments for the Public Prosecution, because this legal right is inherent to the accused before the prosecution.

What is happening in the State Security Prosecution is an incomprehensible matter, as the Public Prosecution, especially the State Security Prosecution, refuses to accept appeals against detention orders submitted by many defendants. This is a violation of the Code of Criminal Procedure article 166. It has become a regular message for the lawyers to inform the families of pretrial detainees that they must wait for the prosecution to allow appeals, As if the matter is a gift from them and not a right granted by law.

Examples:

- Case No. 1356 of 2019

It is the case in which blogger and activist Alaa Abdel Fattah, human rights lawyer Mohammed Al-Baqer, and video blogger Mohammed Oxygen are. All their lawyers suffered for months from not being enabled to appeal the detention orders issued against the defendants on the pretext that all appeals inside the prosecution are suspended!

- Case No. 488 of 2019

It is also a case involving a large number of political activists, lawyers, human rights defenders, journalists and students imprisoned pending it. Among them ANHRI’s rights lawyer Amr Imam, journalist Khaled Daoud, journalist Solafa Magdy and her husband photojournalist Hossam Al-Sayyad. Their lawyers were unable to appeal their detention orders, Since the date of their arrest and for many months, due to the “State Security Prosecution suspending appeals,” which is a polite term instead of saying “the prosecution violates the law.”

- Profiting financially from prisoners and detainees

At the beginning of this year 2021, the Arabic Network for Human Rights Information issued a report on the arbitrariness of the prison administration with regard to bringing in food to prisoners and pretrial detainees.([5])

The report questioned the possible reason for such arbitrariness, and the reasons behind depriving prisoners of obtaining their needs of food, hygiene and personal necessities. The conclusion of the report raised a question about the reasons for preventing bringing in food despite this practice being against the law? The law states clearly that pretrial detainees have the right to bring any food from outside. ANHRI believed that this arbitrary ban would be the result of one of three possible reasons:

The first: is the threat to national security.

The second: is the profit from trading with prisoners.

The Third: is to abuse pretrial detainees.

ANHRI expressed that it is inclined towards believing that the third reason is more likely to be the real reason, as it is a link in the chain of violations in prisons

But we were wrong:

ANHRI found out, after holding meetings with some prisoners’ and pretrial detainees’ family members that the reason of profiting financially which had been previously excluded, is a valid possibility. Preventing families from bringing in food and hygiene tools is a source of financial profit for the Ministry of Interior at the expense of prisoners’ sufferings and the suffering of their families.

ANHRI ruled out this reason, because it means that the interior ministry has sunk too low. The surprise was, that the reason was not only profit, but also exploitation; the canteens in most prisons sell foods, goods and tools, at prices higher than market prices outside prisons.

This was announced by many former prisoners of conscience, as well as some families whose relatives are still imprisoned.

- A prisoner’s wife mentioned that her husband bought three pieces of falafel for fifteen Egyptian pounds inside the prison, which means that it cost him five Egyptian pounds each, while its price outside prison ranges between fifty piasters and three Egyptian pounds, depending on the location and type of the restaurant that serves it.

- A former prisoner of conscience recounts that he used to buy a pack of Cleopatra cigarettes for “30 Egyptian pounds”, that is 150% more than its real price. He also was obliged to buy a box for himself and another box for the warden, meaning that he had to pay about 60 Egyptian pounds to buy a pack of cigarettes while its real price is Egyptian 20 pounds.

There are many examples of profiting and investing at the expense of the freedom of prisoners, which is the cruelest explanation. It also proves the absence of humanity in the act of preventing the entry of food and tools for prisoners. They simply oblige the prisoner to buy them from the prison canteen, at higher prices, no comment.

- Excuses and the on-paper renewal for pretrial detainees

“On-paper renewal” is a new expression is being used repeatedly in courts and prosecution offices since the beginning of the 2019. It means ordering the extension of the pretrial term on papers without the presence of the individual due to the Ministry of Interior’s announcement that they were unable to transfer the pretrial detainees to the prosecution office or the court that is considering renewing the detention.

Despite the illegality of this procedure, as the law allows the release of a precautionary detainee at any time without his presence, but to renew the detention it is mandatory for the defendant to be present and give his defense! And that is in accordance with the text of the article 136 of the Egyptian Code of Criminal Procedures, which states that:

“Before issuing a detention order, the investigating judge must hear the statements of the Public Prosecution and the defense of the accused, and the detention order must include a statement of the crime attributed to the accused, the penalty prescribed for it, and the reasons on which the order is based. The provision of this article shall apply to orders issued to extend preventive detention.” According to the provisions of this law)

However, the Public Prosecution and some judges who are considering the detention renewal orders of the accused have expanded this procedure. It has become customary for lawyers and families of the accused and for the accused themselves to know that their imprisonment has been renewed even though they did not leave the prisons in which they were kept in and did not present any defense that might lead to their release.

There are a huge number of examples of cases and defendants whose imprisonment was renewed without their presence, such as:

- Case No. 1739 of 2018 Supreme State Security Prosecution, in which journalists Mohammad Mesbah Jibril and Abdel Rahman Awad are accused

- Case No. 470 of 2019 Supreme State Security Prosecution, in which Islam Fathy is accused

- Case No. 1739 of 2018 Supreme State Security Prosecution, in which poet Hamada Siddiq, Thaer Izzat, and novelist Ibrahim Mohammed Ibrahim are accused.

Numerous examples of cases in which imprisonment was renewed without the presence of the defendants appear in ANHRI’s report “We apologize: We won’t respect the law today” About the phenomenon of security pretexts and lawlessness in Egypt for pretrial detainees ( [6])

- The rotation of defendants and extending their pretrial detention pending new cases

Rotation is a new term, used to refer to cases in which a decision is made to release a prisoner or pretrial detainee, and while processing the release procedures, he/she is surprised to be summoned to the prosecution for investigation pending charges in a new case. Sometimes they are facing the same old charges, or new ones, may be the prisoner finds himself accused of a crime that happened while he was in prison which practically makes it impossible for him to have been involved in it. The detainee may gain his freedom for a few days or months before being re-arrested and imprisoned again. In other cases the detainee may not see the sun of freedom even for an hour and finds himself transferred to prison again.

Examples of these victim prisoners include:

- Human rights lawyer Ibrahim Metwally, who was imprisoned first pending case No. 900 of 2017 Supreme State Security. In 2019, he was ordered to be released after two years of custody imprisonment, he was charged in a new case: No. 1470 of 2019 State Security. He is still imprisoned for nearly four years now.

- The cases of Dr. Abdel Moneim Abul-Fotouh, Mohammed Al-Qassas, Ola Al-Qaradawi, Shadi Abu Zaid, Mohab Al-Ibrashi, and other pretrial detainees. ([7])

Third: Using COVID-19 pandemic to oppress prisoners

Unlike most countries of the world, which expanded releasing prisoners, fearing that the spread of the COVID-19 pandemic among prisoners and getting into a disaster, The Egyptian state used the situation to practice further repression and violations.

This led to more depression within the Egyptian society and among the families of detainees and those concerned with freedoms and even the detained people themselves. It means an increase in the rivalry between the authorities and those concerned with freedoms and the rule of law.

Among the violations that have spread, during the COVID-19 pandemic:

- Partial lockdown, then public opening, random arrest of citizens, and on paper renewals in violation of the law. It happened with many people including human rights lawyer Mohsen Bahansi, journalist and researcher Shaimaa Sami, academic Dr. Laila Soueif and her sister Dr. Ahdaf Soueif, Dr. Rabab Al-Mahdi and activist Mona Seif.

- The death of former prisoner journalist Mohammed Munir a few days after his release.

- Renewal of detention without hearing the statements of the defendants or their lawyers, and sometimes despite the presence of the defendants inside the court building, such as Yasser Antar Abdul Latif and activist Nermin Hussein.

- Failure to transfer suspects to courts and denial of their visitation rights despite the general opening of state institutions and despite the fact that the pandemic has not ended.

Fourth: Preplanned prison visits to beautify the image of the interior ministry

When one searches the web looking for the words prisons, prisoners, prison inmates, or Tora or Al-Marg prison, for example, you will be amazed by the huge number of news articles that result from the search. Most of which are news praising the conditions of prisons, the happiness of inmates, and the prisoners’ gratitude to the Egyptian Ministry of Interior, and the results of visits arranged by the Ministry of Interior for journalists, media professionals, human rights organizations, and even university students for prisons. The results also will include thanking the ministry for preserving human rights in prisons.

These are the most widespread news, as a result of the ownership of the state apparatus and its institutions to most media outlets, in addition to its control over most of the remaining media, whether due to the fear of imprisonment or of blocking and restrictions.

But by narrowing the scope of the search, using methods to bypassing blocking, and hearing the testimonies of former prisoners or their families, or the few remaining independent human rights organizations, one learns about and sees a completely different picture from what is being promoted.

The visits approved by the Ministry of Interior and the Public Prosecution are carried out to allow specific human rights institutions, headed by the National Council for Human Rights. It is a governmental and national council whose legal mandate had expired in 2017, that is, four years ago. As a result of its remarkable role in polishing the image of the Interior ministry and complicity in human rights violations, it continues to this day in violation of the law, because its performance is satisfying to the regime.

The situation is different for some institutions called “GNGOs”, the term was coined to refer to organizations complicit on human rights violations. They work to polish the image of the regime in accordance with the agenda of state agencies and are used to attack and defame independent organizations.

The situation may differ slightly with visits in which media professionals and journalists are allowed. It is normally fewer and requires very careful preparation. It also requires the pushing away of prisoners with severe complaints, not only from meeting the visitors, but also from the entire prison. This happened during one of these visits to Al-Qanater prison towards the end of 2020, when female prisoners of conscience with complaints were taken out in order to allegedly complete their sentence “despite the lack of a real investigation with them” during the visit.

The goal that ANHRI saw was to remove them from prison during the visit of some journalists, accompanied by some members of the National Council. The situation made three members of the National Council issue a statement in which they expressed that this visit aims to beautify the image of the prison administration and that it is a promotion by the Ministry of Interior of an unrealistic situation. ([8])

ANHRI monitored 24 visits during the period from 2017 to December 2020. The visits were arranged for delegations that the Interior Ministry calls “human rights and civil society delegations” or members of parliament. None of these visits included any independent human rights organizations or independent human rights activists, whether local or international. The Ministry of Interior’s justification is that most of these independent organizations are “unregistered”. Such justification can not simply be accepted because they are the same organizations that were invited in the past to visit prisons, and even train the Ministry of Interior’s officers themselves, including ANHRI, the Egyptian Initiative for Personal Rights, among others.

So the famous image of a human rights defender remains to be the one visiting prison and praising it while eating. It is a similar image to a scene of a famous Egyptian movie “The innocent” depicting a human rights activist playing the same role in beautifying the image of the regime in a flagrant contradiction to the real situation.

Fifth: Number of Prisons in Egypt

- Number of prisons in Egypt before January 25 (43 prisons)

The number of the main Egyptian prisons before the January Revolution reached 43, distributed in 18 governorates. You can learn about them, their names and their locations by browsing the previous ANHRI report on prisons, issued under the title “There is room for everyone: Egypt’s prisons before and after the January revolution,” which monitors the number of prisons until the beginning September 2016 by visiting the following link; https://anhri.net/?p=173532&lang=en

- New prisons since January revolution till September 2016 (18 prisons)

The number of official decisions to establish prisons after the January revolution and until September 2016 reached 19 prisons; the constructions began with the establishment of Wadi al-Natrun Public Prison 1 in October 2011, reaching to South Beni Suef Central Prison in July 2016.

The list includes:

- Wadi Al-Natrun Public prison 1

- Qantara public prison

- Beni Sweif central prison

- Gamasa leeman

- Gamasa highly secured public prison

- Menia leeman

- Menia highly secured prison

- The central prison in Benha second station

- Highly secured prison 2, Tora

- Giza Central prison

- Nahda Prison

- 15 May prison

- The central prison in security forced commnd, the prison of Kilo 10.5

- Khosos prison

- Edko prison

- Baghdad village prison

- Khanka prison

- Obour prison [9]))

- South Beni Sweif prison

You can get more information on every prison and details in the report; there is Room for Everyone; https://anhri.net/?p=173532&lang=en

- New prisons since 2016 till March 2021 (17 prisons)

Since the aforementioned report was issued in September 2016, which mentioned 18 new prisons, decisions were issued to establish 17 new prisons until March 2021:

- Ataqa prison in Suez

Establishing a central prison called Ataqa Central Prison in the Suez Security Directorate based on the decision of the Minister of Interior No. 4284 of 2016, on November 3, 2016

- A prison in Tanta third station

Establishing a central prison named “Central Prison, Tanta Police Department III”, affiliated to the Gharbia Security Directorate, based on decision No. 621 of 2017, on April 1, 2017

- Giza General Rehabilitation Prison

Designating the Military Rehabilitation Prison in Al Qatta to be a general prison called “General Rehabilitation Prison” based on the decree of the Minister of Interior No. 1473 of 2017, on September 6, 2017

- Matrouh General Prison

Amending the purpose of allocating a piece of land in Matrouh from establishing a central prison to establishing a general prison, based on decree of the Minister of Interior No. 2208 of 2018, on December 13, 2018

- Karmouz Prison in Alexandria

The establishment of a central prison in the Karmouz Police Department, by decision of the Minister of Interior No. 4473 of 2016, on November 27, 2016

- Al-Qusiya Central Prison in Assiut

Establishing a central prison named Central Prison at the Qusiya Police Station of Assiut Security Directorate in accordance with decree No. 1620 for the year 2017, on November 5, 2017

- New Assiut Central Prison

Establishment of a central prison called “Central Prison in the New Assiut Police Department” based on decree No. 1227 of 2017, on July 24, 2017

- Oseem prison in Giza

The establishment of Oseem Prison by Decree of the Minister of Interior No. 1495 of 2018, on October 8, 2018

- The Central Prison in Assiut

The establishment of the Central Prison for the Central District in Assiut by decision of the Minister of Interior No. 182 of 2019, on February 3, 2019

- Mahallet Damna prison in Dakahlia

Major General Mahmoud Tawfiq, Minister of Interior, decided to establish a central prison called “Central Prison at the Mahallet Damna Police Station”, whose jurisdiction includes the Dakahlia Security Directorate, by decision of the Minister of Interior No. 479 of 2019, on March 14, 2019

- October Central Prison in Giza

The establishment of October Central Prison of the Giza Security Sector based on decree of the Minister of Interior No. 1053 of 2020, on July 5, 2020

- Sanhour Central Prison in Fayoum

Minister of Interior issued decision No. 268 of 2021, to establish a central prison in Sanhour Police Station in the Fayoum Security Directorate, with the name of “Central Prison attached to Sanhour al-Qibli Police Station”. Its jurisdiction includes the Department of Sanhour al-Qibli Police Station (The decision was published in the Official Gazette on February 18, 2021.

- Youssef Al-Siddiq Central Prison in Fayoum

Interior Minister issued decree No. 269 of 2021, to establish a central prison at Yusef Al-Siddiq Police Station in the Fayoum Security Directorate under the name “Central Prison of Yusef Al-Siddiq Police Station”, and its jurisdiction includes the Police Division Department west; “Abshway – Yusef Al-Siddiq – Al-Shawashnah. The decision was published in the Official Gazette on February 18, 2021.

- Belbeis Central Prison

- Central Prison of the third station in 10th of Ramadan

- Tenth of Ramadan Central Security Forces Prison

The latest three prisons, decided to be established by Resolution No. 378 of 2021, and published in Official Gazette No. 57 on March 10, 2021, regarding the establishment of (3) central prisons in the Eastern Security Directorate.

- Al-Stamouni Central Prison

Interior Minister issued decree No. 420 of 2021 to establish the Central Prison at Al-Stamouni Police Station in the Dakahlia Security Directorate. The decision was published on March 18, 2021.

- The total number of new prisons in Egypt during the decade that followed the January revolution (35 prisons)

According to the findings of ANHRI after monitoring the official decisions published in the Official Gazette and the Egyptian Gazette, the number of new prisons during ten years followed January Revolution has reached 36. After a decision was issued to cancel the establishment of the Central Prison, the number of new prisons became 35.

Sixth: Estimated numbers of prisoners and detainees in Egypt (around 120 thousand)

- Examples of inconsistency and lack of transparency

The head of the Prisons Authority, Major General Mustafa Baz, the assistant of Interior Minister for the Prisons Authority sector, estimated the capacity of prisons at 75 thousand prisoners in 2013. This was before adding about 30 new prisons since this time, including two prisons, each with a capacity of 15 thousand prisoners, according to a statement to Al-Watan newspaper. ([10])

- President Sisi while visiting France in December 2020 declared that prisons have places for only 55 thousand ([11])!

- In November 2019, the journalist “Nashaat Al-Daihi”, close to the security services, announced that the number of prisoners in Egypt is 114,000. Among them 84,000 have been sentenced to final verdicts and 30,000 under pretrial detention ([12]). This is a number different from what journalist Mohammed al-Baz announced in Al-Fajr newspaper on the same day mentioning a smaller number with four thousand difference.

- The spokesperson for the United Nations High Commissioner for Human Rights announced in April of the same year that Egypt has more than 114,000 prisoners. He called upon Egypt to release prisoners of conscience and stop the overcrowding in prisons ([13]).

- ANHRI’s estimation for the prisoners and pretrial detained people held in Egypt;

- The total number of perisoners and pretrial detained people is about 12 thousand divided as follows;

- The number of political prisoners and detainees in Egypt is about 65,000 prisoners and pretrial detainees. They are devided into

- 26 thousand and pretrial detainees

- 39 thousand convicted prisoners

- Number of criminal prisoners and pretrial detainees for common criminal reasons is about 54,000 prisoners and pretrial detainees. They are divided into;

- 11 thousand pretrial detainees

- 43 convicted prisoners

- The total number of convicted prisoners is about 82 thousand

- The total number of pretrial detainees is about 37 thousand

- The number of people held for no clear reasons is about 1000 detainees.

ANHRI was unable to determine the reasons of detention or the legal status for about 1000 detainees monitored in different police stations such asp Dar Al Salam, First Settlement, Al Matareya, Al Basateen, Atfih Center, Ain Shams, and Nasr City, as well as some headquarters of the National Security Investigation such as Abbasiya, Sheikh Zayed, Al Maasara, Shubra El Khaima and Alexandria Security Directorate.

- These estimations

- These estimations are according to ANHRI’s monitoring till March 2021. It was based on data collection and calculation of the numbers included in the statements of cases that were considered by the Institute of Police Secretaries and the State Security Prosecution during the years 2019, 2020. It also monitored new cases during the first three months of 2021 and the numbers of prisoners published by some official media outlets or those close to the state officials. In addition to the estimation of ex-prisoners released from prisons or police stations or national security headquarters. As well as meetings with some sources working for the interior ministry who preferred not to be named, and through visits to some prisons and departments, and also the numbers of releases, many of which were criminal cases.

- ANHRI noticed that Most prisoners and detainees are concentrated in the basic prisons such as “Tora, New Valley, Gamasa, Minya, Wadi Al-Natrun, Burj Al Arab, Al-Qatta, Al-Wadi Al-Jadid, Lyman Abi Zael, 15th May, Fayoum”, which includes about 75 thousand prisoners and pretrial detainees, while the rest of the prisons and detention headquarters have about 45 thousand prisoners, and pretrial detainees, and detained.

for pdf

for word

[1] ANHRI report; There is Room for Everyone… Egypt’s Prisons Before & After January 25 Revolution, last checked on 4th January 2021, https://anhri.net/?p=173532&lang=en

[2]– Almasry alyoum newspaper, published on 17 January 2017, browsed on December 2020 https://www.almasryalyoum.com/news/details/1073341

[3] The website of casation court, published on March 2020, browsed on September 2020 https://www.cc.gov.eg/legislation_single?id=402456

[4] Alwatan newspaper, published in May 2020, browsed on 7 december 2020 https://www.elwatannews.com/news/details/4762835

[5] Grapes, do they pose a threat to national security? A report about the prison authorities’ intransigence in delivering food to prisoners published in February 2021, browsed on 30 March 2021 https://www.anhri.info/?p=22006&lang=en

[6] We apologize: We won’t respect the law today “About the phenomenon of security pretexts and lawlessness in Egypt” published on 18 August 2019 and browsed on 3 March 2021 https://www.anhri.info/?p=10415&lang=en

[7] Report: Recycling Detainees Of releasing detainees, then incarcerating them again for new cases, published in February 2020 and browsed on 3 March 2021 https://www.anhri.info/?p=14874&lang=en

[8] Darb website; statement by 3 members of the human rights council published on 30 December 2020, browsed on 7 march 2021 https://daaarb.com/%D8%A8%D9%8A%D8%A7%D9%86-%D9%84%D9%80-3-%D9%85%D9%86-%D8%A3%D8%B9%D8%B6%D8%A7%D8%A1-%D9%85%D8%AC%D9%84%D8%B3-%D8%AD%D9%82%D9%88%D9%82-%D8%A7%D9%84%D8%A7%D9%86%D8%B3%D8%A7%D9%86-%D8%AD%D9%88%D9%84/

[9] In November 2016 the minister of interion decided to annule the establishment decision, manshoorat website, browsed on 6 march 2021

https://manshurat.org/node/13568

[10] The head of the Prisons Authority, Major General Mustafa Baz in an interview to Alwatan newspaper published 27 August 2013, browsed on 4 March 2021 https://www.elwatannews.com/news/details/284505

[11] Interview with French Le Figaro on 8 December 2020, browsed on 4 March 2021

translated into Arabic on 8 december 2020, browsed on 4 march 2021

[12] almasry alyoum newspaper on 11 November 2019 browsed on 4 march 2021

https://www.almasryalyoum.com/news/details/1442357

[13] High commissioner Office, Media statement published on 3 April 2020, browsed on 12 March 2021

https://www.ohchr.org/AR/NewsEvents/Pages/DisplayNews.aspx?NewsID=25772&LangID=A